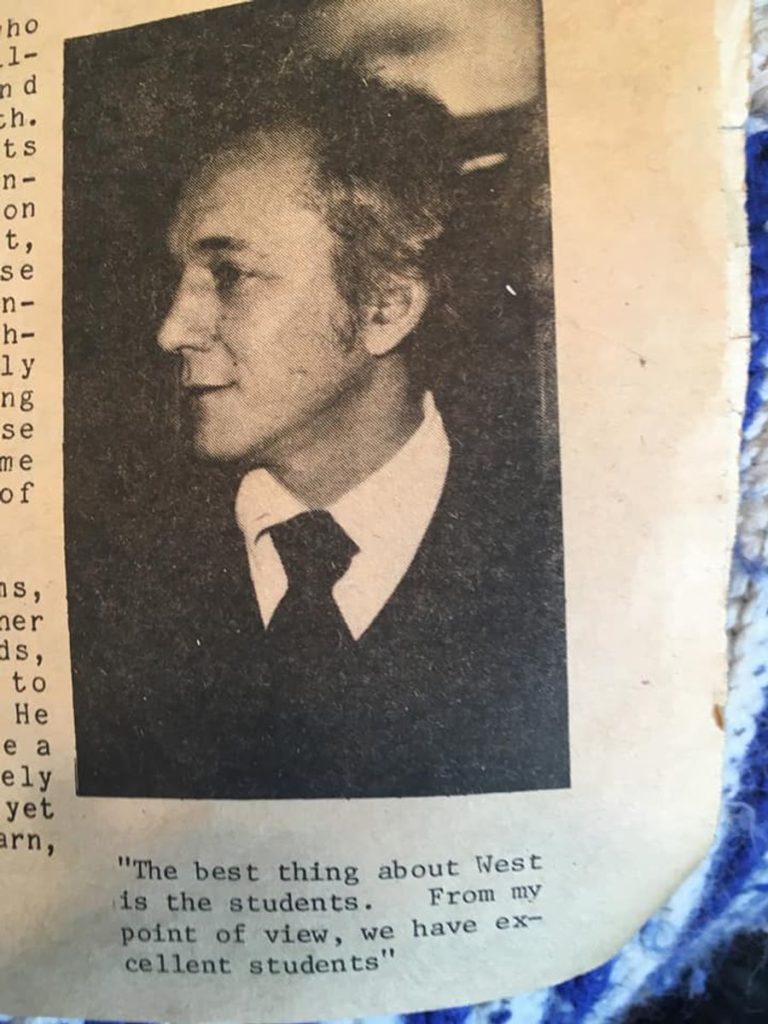

I had a wonderful Algebra II teacher named Louis Gmeindl.

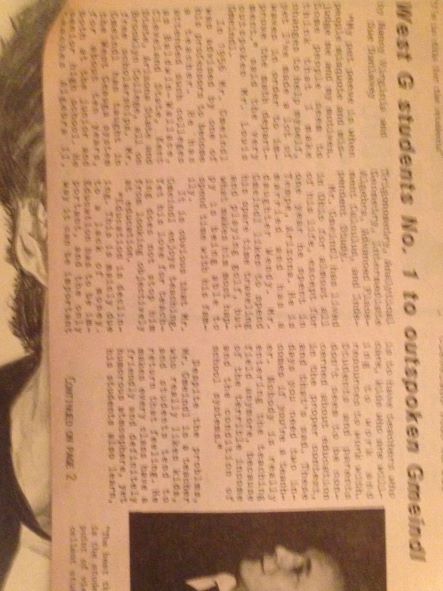

He was the Dr. Gregory House of West Geauga High School.

People were terrified of his class. Me, I thought everything he ever did was hilarious. Then again, he rarely picked on me.

Perhaps the only time I sort of felt the brunt of his sarcastic and venomous wit was the first day I met him. The period before his class, I had Latin all the way across the building. We couldn’t hear the bell, so I wound up being 3 or 4 minutes late to my first class with the terror of the math department. When we showed up, he had all the students lined up on a wall as if he was about to lay a firing squad on them. When we showed up, he immediately singled me out.

“Laidman, I’ve heard of you.”

The rest of the year went like this. I breezed through his class like I was listening to the Howard Stern Show while many of my friends were trying to deal with the fact that they were about to get their first C or lower.

Many people who got their grades through hard work were still having trouble keeping up because the material was so hard and Gmeindl’s pace so insistent.

Here’s how slanted things were for me compared to the rest of the class.

People panicked before every one of his tests, but he would bet me a quarter on every test. To win the bet, I had to get a perfect score. It was a little tacky, considering that even my brilliant friends were struggling towards a B in the class.

My friend Doug was among the best math students in my grade. He wound up attending MIT. He didn’t have enough time to finish one test, so he wrote at the bottom of his paper, “I think it’s really unfair for you to make the tests so hard just to win a quarter from Brad!”

Lou Gmeindl never collected homework. He simply told his students that they’d have no chance of passing the class if they didn’t do the task.

“Go ahead, skip the homework. I dare you!”

I never did the homework. Well, sort of. Everyone should have hated me for breezing through as they were drowning, but they were too busy phoning me for help.

I never formally did the homework, but I got so many calls for help that it was almost as if I’d done each homework assignment five or six times.

Sure, I may have been more intelligent than them. Still, I was pulling everyone else through the class, too, so I was spending more time on the material.

I was practically co-teaching the entire class.

Louis Gmeindl would go on these great rants. The one time I may have gotten the best of him was after this one.

“You know what I want to know? How come none of your parents buy you chalkboards and erasers to play with? They’re buying you all this useless crap when they should be making you learn. Can someone tell me why that is?”

This time I had the answer.

“Because they want us to like them!”

Even Mr. Gmeindl laughed with us at that one.

Another great rant:

“You guys all want to go to college, but you’ll completely waste the opportunity. Your parents would be better off giving you the money and telling you to open a Pizzeria. In four years, you all will be in debt. You’ll probably have learned nothing worthwhile because you’re all lazy and don’t care. Meanwhile, I’d own a pizza place and be making cash money every day.”

He knew what he was talking about. He owned his own gas station and often gave the impression that the only reason he worked at the school was his own personal irritation that his students weren’t learning math the way he wanted.

He was twice as tough as most of the teachers at the school, but he was challenging, and he cared twice as much about his students as most of the others did.

“You know why I’m as smart and educated as I am,” he crowed one day. “It’s because I worked hard. I was so dedicated that when I was at college, I never wasted a second. When I was walking to class, I was learning memorization in my head. Not a second wasted.”

I could understand this because I’m famous for never being without something to read and walking when I’m reading.

I have a pathological need to be infusing myself with new knowledge or something to fill my head with at all times. For Mr. Gmeindl, this was a tribute to his hard work ethic. For me, it was just a way to keep my brain from being angry with me.

I was maybe one of the least respectful students in high school, but I really respected Mr. Gmeindl. To this day, I would never dare to call him or refer to him as Lou.

I let him down once, and he let me know it dramatically. A yearly standardized test was given to the upper bank math classes in 11th, and 12th grade called the MAA.

It was a tough test, and the highest scores would be posted on the math office doors.

The first year I took it, I didn’t take it all that seriously. This test was even too hard for me to finish. I just answered C for the last ten questions, which wasn’t necessarily a good practice because missing a question was worse for you than leaving it blank.

Louis Gmeindl saw and let me have it. “All those brains, and you do something like this.” When the scores came out, my name was at the very bottom of the list.

Now, I still outperformed all of the other 11th graders. The 25 or so names ahead of me were all seniors, but Mr. Gmeindl ensured that I would be at the very bottom when the list came out to punish my lack of serious intent.

The following year I took it seriously and came in first. I don’t remember if Louis Gmeindl praised me for this. He probably just expected nothing less of me. I’m sure he let me know that he had taken the test himself and scored higher than me!

My debate partner that year was a terrific bright goofball with the equally wonderful name of Michael Stuntz.

Stuntz was a year ahead of me, and while he was taking the test, he noticed a pattern in the answers and decided to go with it.

Doing poorly on the MAA didn’t affect your grades, so he decided to answer all the multiple-choice questions DEAD BABEE. His entire test paper said that D E A D B A B B E E D E A D B A B B E E .

Much to the math department’s chagrin, Mike Stuntz finished with the highest score on the MAA that year. Imagine that he managed to earn the title of most brilliant math student in the school, and he got into trouble doing it. That was Mike Stutz.

My favorite Gmeindl moments didn’t even happen in his class. I took Social Studies with Gmeindl’s buddy, who coached the baseball team. His name was Mr. Mack. Mr. Mack was a riot. It was the easiest class I ever took, but it was fun.

Usually, these two teachers were separated by their different departments. This one time, Mr. Mack was getting to teach in the room next door to Gmeindl’s math class (I think he taught every class in the same room, which was very rare at my school and showed his status).

Mr. Mack was the kind of teacher who felt that the classes were ten minutes too long, so after about forty minutes, he’d stop teaching and goof around with us for the last ten. Mr. Gmeindl would never do this. He probably thought his classes should have been twice as long!

But Mr. Gmeindl wasn’t above giving his class challenging problems to work on while he slipped next door to discuss how lazy we all were and last night’s poker games.

“These kids don’t realize how easy they have it nowadays!”

“Give them a break. Zukowski is too busy trying to win football games to worry about your high standards!”

They were practically Jack Benny and George Burns most of the time. I’m not sure it’s possible to have two teachers more philosophically opposed to each other’s methods. Still, they both had a sense of humor and kept young faux-mocking their students.

Mr. Mack also took great pleasure in the fact that he could teach this class with one eye on the boy’s bathroom. Whenever some shady-looking group of kids would enter the bathroom, he would pounce in and hilariously accuse them of smoking.

It was a sort of entrapment, but it was always funny.

After I graduated, I went back to see Mr. Gmeindl, and he complained about the lack of math talent he was dealing with.

“The only one worth anything is that one over there, and he doesn’t care.”

He was talking about the younger brother of one of my best friends. He was taking a nap during lunch, his head down upon one of his books, and you can bet Louis Gmeindl said it loud enough to wake him back up!

Mr. Gmeindl praised him as the best and leveled him down to size simultaneously.

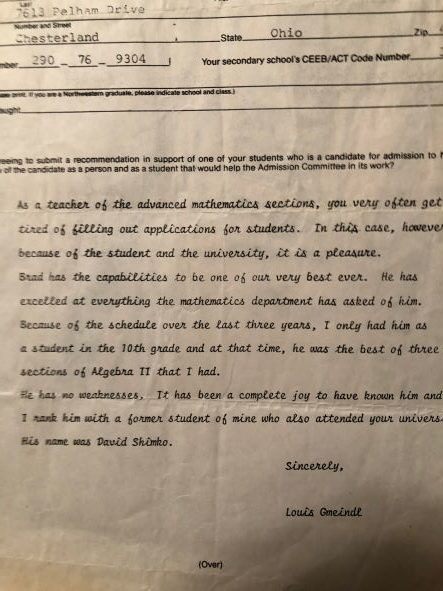

He wrote me a beautiful recommendation for my college applications. Unlike other teachers, he showed it to me when he was done. It was his way of letting me know forever that he really liked and appreciated me and my efforts. I still have it!

Mr. Mack was a good friend of Thurman Munson’s in college.

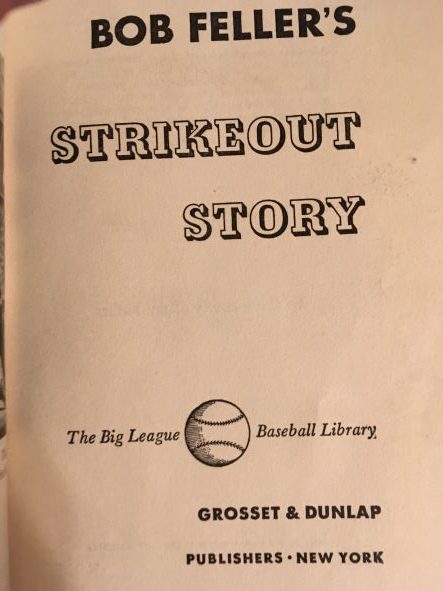

I always wanted to own Bob Feller’s house in Gates Mills. Had I listened to Mr. Gmeindl, I likely would own it now.

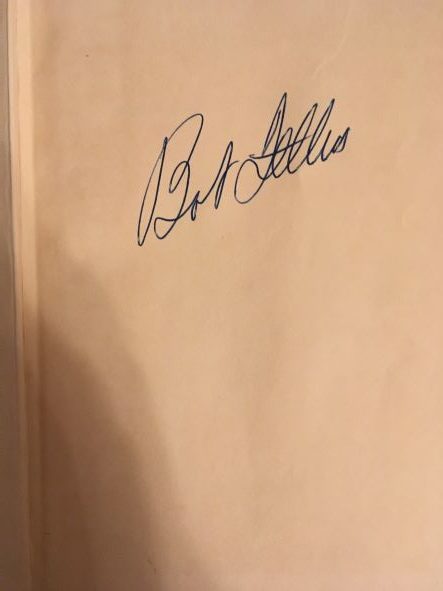

Louis Gmeindl became Bob Feller’s personal manager. Mr. Gmeindl drove Feller to the stadium every day for five years until the day he died.

My algebra teacher actually reduced the value of the book I still own from the early fifties that my dad had signed by Bob Feller personally around 1951.

Mr. Gmeindl probably got a laugh out of having Feller sign so many autographs that it may have cost me money on something I would never sell.

Mr. Gmeindl had a standing rule that if you wanted help in his class that he would stay as late as you wanted. He would last until midnight if you would.

If you came, he would have you at the blackboard the entire time, but he felt that life was pressure and insisted that you be ready for it.

That was the deal he’d stay until you learned. If you learned, he would remain until he dropped.

Last I heard, he was retired and living the easy life in Arizona.

I miss him and respect him every day.

He loved me but would never admit it.

We both knew that, and it went both ways.

It was understood and never needed to be said.

What else can I say?

Lou Gmeindl will always have my ultimate respect and love until the day I die.

Thank you

Thank You, I don’t think I had a choice whether to have him – he knew me the second I walked into his class – late – through no fault of my own 🙂

I had him a year before Brad. Best teacher I ever had. I may have even told Brad to try to get Mr. Gmeindl. After all, Brad lived a short walk through the woods from me.

I was NOT his star pupil. I had him for the last quarter of 7th grade math, (his first quarter back at West Geauga) My brother had had him and told me horror stories about him. I got along great with him. Then I had him for geometry the same time as Margaret. I worked my butt off for him. As I went through high school, I would come back down to the jr high and he’d tutor me. I listened to him teach the remedial math class about probability. To this day as I help my nieces and and nephews with statistics, I can still hear him teaching. He was THE BEST instructor I have ever had.

Thank you for writing this. I too had Mr Gmeindl for geometry in 74(?). Truly changed my life. I loved every minute of his class and it was like an awakening ( having been uninspired and thus average before that ). Because of him I went to CWRU in physics and math and have had a great career. Thank you Mr. Gmeindl!

I had Gmeindl for 9th grade geometry in 74-75 and the for calculus in 77-78. He remains an inspiration to me, and I feel that I too was his “best” that year. Since then I got a PhD in mathematical finance, have taught at Harvard Business School, and worked at JPMorgan before starting my own risk management consulting practice. Thank you, Lou Gmeindl!