I have a friend named Grant Taylor, who used to be a standup comedian. My favorite one liner of his went something like “Hitler liked to paint. That doesn’t make it wrong.”

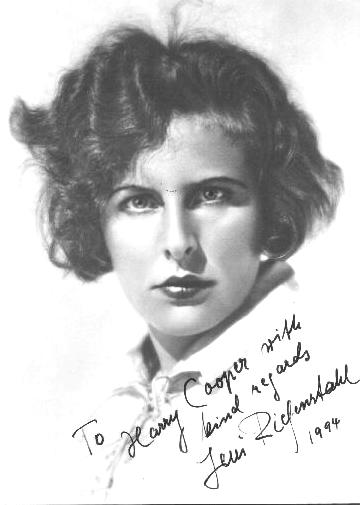

I couldn’t help but think of that when I popped over to that bastion of modern culture, the E channel’s online news, and read “Leni Riefenstahl, Adolf Hitler’s favorite filmmaker and the last of Germany’s infamous Nazi-era figures best known for such Third Reich propaganda films as ‘Olympia’ and ‘Triumph of the Will,’ died on Monday, just weeks after turning 101.” That’s not necessarily inaccurate, and believe me I’m not expecting George W. Bush to offer his condolences like he did with Bob Hope, but what a depressing tag for one of the most amazing women of the 20th Century. “Adolf’s favorite filmmaker.”

Ironically, although she was much more than that, in the end that headline got so big that none of the fine print ever really mattered again. After World War II ended, Reifenstahl was dropped from the film world faster than Hertz dropped OJ Simpson from their board of directors.

If you haven’t already seen it, you must check out Ray Muller’s fascinating and brilliant documentary “The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Reifenstahl.” Here’s the one-minute summary. Imagine Sharon Stone gives up acting and becomes Martin Scorcese, despite the fact that she exists at a time when women filmmakers are practically non-existent, and then in her prime is suddenly stripped of the ability to ever work in her chosen field again.

Reifenstahl was a beautiful young dancer who started appearing in the German films of Arnold Frank. These, for the most part, consisted of her climbing snowy mountain peaks barefoot – and you thought Renee Zellweger was a good sport for putting on a few pounds to play Bridget Jones. It sounds almost like a Paul Bunyon type legend that couldn’t possibly be true, but it’s all on film and then again this was a woman who was still deep sea diving into her ‘90s.

Using what she learned from Frank, Reifenstahl started making her own films. Had she been born in America, Reifenstahl would likely have given Katherine Hepburn’s legend a run for her money. Nevertheless, her fate was to be an artist in the center of the Nazi hurricane. Reifenstahl’s biggest historical sin was, that in a time of propaganda films, she made the greatest one of them all. Her 1934 film, “Triumph of the Will,” made Hitler’s Nuremberg rally look like an assembly of the Gods. It makes D.W. Griffith’s glorification of the Klan in “Birth of a Nation” look like child’s play in comparison. Imagine Steven Speilberg commissioned to film a feel good epic on life in hell by Satan, and not realizing the subsequent impact of his actions. Imagine Oliver Stone dedicating the best work of his career to filming cigarette commercials.

“Triumph of the Will” is both an amazing cinematic achievement and perhaps the largest lapse in judgment by a brilliant artist in modern history. There is a fascinating scene in Muller’s documentary as he films Reifenstahl looking at some of her innovations from the filming of “Triumph.” In almost the same breath, she insists that the film was a horrible mistake that destroyed her artistic life, all the while proudly explaining how she rigged rising mechanical cameras to the Nazi’s flagpoles in order to make the cascading horde of marching devils all the more dramatically impressive.

Reifenstahl, until her death, would insist that she wasn’t a Nazi and only made “Triumph” for Hitler with the understanding that she would never have to work for the Nazis again. Her culpability in what followed is perhaps one of the most fascinating artistic questions of all time. How exactly do we judge the artist who, either by choice or mistake, surrenders her talents to the purveyors of evil? Muller’s film shows an aged Reifenstahl, who refuses to go down lightly. An irascible presence, who refuses to completely acknowledge her sins. A titan destroyed by the tides of history, who can barely admit to herself the damaging impact her work had on the course of time. To her, “Triumph of the Will” was a job that she fulfilled to her utmost and not inconsiderable ability. This is what happens when art and the real world collide and I for one am almost completely incapable of knowing exactly how best Reifenstahl needs to be judged by the writers of history. It was a strange time. One where Frank Capra was filming America’s answer to “Triumph” – “Why We Fight.” “Why We Fight,” itself is a fascinating bit of oxymoron. Film propaganda in favor of ethnic tolerance that still manages to refer to the Japanese, as Hitler’s bucktoothed pals.

The simple fact, though, is that she was a remarkable woman, both in talent and vigor. She would go on to film the official record of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, Olympia. Olympia is a brilliant combination of sports reporting and the art film that saw Reifenstahl innovate innumerable brilliant new ways to show the athletes in action. The film’s underlying theme comparing the world’s best athletes to the perfection of the ancient Greek Gods would tragically be misinterpreted through the ages as yet another argument for the pure blood of the Aryan ideal even though the film manages to justly celebrate the superiority of Jesse Owens that Hitler did his best to ignore.

After World War II, no one wanted anything to do with Reifenstahl. She never made another movie. Nevertheless, she was hardly the type of weak flower to just fade into the woodwork. Her later years saw her communing and documenting the life of Africa’s Mesakin Nuba tribe. Muller’s film includes footage of Reifenstahl lovingly holding a young black African baby, an image far from the catcalls of those who would portray her as, at best, a Nazi tool.

Reifenstahl’s blackball seems incredibly cruel in an age where teen rapist Roman Polanski is personally delivered his Academy Award by Harrison Ford and accused child molester Woody Allen is given a standing ovation at that very ceremony, but then again we are talking about someone associated with the last unanimous faction of evil. In an age, where we strive to be sympathetic in our film portrayals of Russian and Arabs, Nazis are the last easy villains left to the modern film director.

As far as I see it, it’s hard to argue anything less than that Reifenstahl was the most significant woman in film history. Fate will consign her right next to D.W. Griffith. Both unanimous inductees to the Hall of Fame, who at the same time inspire shame in the curators left to populate their displays. The questions about art and it’s effects and responsibilities toward the real world that her life illuminates will continue to fuel heated arguments from historians and filmmakers alike. The moral? If you’re young and talented, be careful whom you work for.